Panel 1 was on the topic of art, science and engineering as sites/places where early experiments in media art took place, most often as a combined form of research and development, focusing on examples of their intersections. The panel was moderated by Edward Shanken, with panelists Michael Century, Stephen Jones, Eva Moraga and Robin Oppenheimer.

Panel 1 was on the topic of art, science and engineering as sites/places where early experiments in media art took place, most often as a combined form of research and development, focusing on examples of their intersections. The panel was moderated by Edward Shanken, with panelists Michael Century, Stephen Jones, Eva Moraga and Robin Oppenheimer.

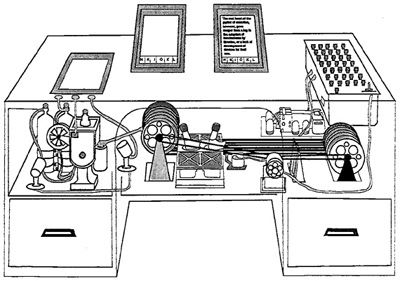

The first presenter, Michael Century spoke about how R.M.Baecker's research on hand-drawn digital animation at MIT's Lincoln Labs lead to the development of the Graphical User Interface (GUI)1. GENESYS was created in the late 60ies and tested by artists of Harvard's Visual Art Center. What was important to the artists was not what could be seen in the frame, but in the behaviour of the tool. Century spoke of this process of refining GENESYS, with the help of artists, as a co-invention between engineer and artist. Alan Kay, researcher at Xerox PARC, saw GENESYS' potential for his own interests, its potential of being an open ended medium with expressive possibilities, similar to clay or paper. The GUI he imagined was just like that: a personal dynamic medium. In his summary, Century thinks the reason for GENESYS' success was that it had worked as a boundary object2 between animation and computer research.

The second speaker, Stephen Jones discussed early experiments in art and technology at the University of

Sydney (from 1968 to 1975). John Bennett, a British Computer Engineer headed the Basser Department of

Computing at the University's School of Physics. The department developed computer graphics for simulations and also made animations for the US airforce, computed algorithms that were recorded frame by frame with a movie camera and later coloured by hand. After visiting the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition in London, Bennett became fascinated by the possibilities of using the computer as a medium for artistic expression. In 1969 he gave a talk on technology and art and encouraged his students to use the computer to make art themselves. Out of this grew a rhizomatic network of students collaborating in media enhanced art projects.

What both Century and Jones wanted to show is the network of relations and flows of influences. Whereas

Century's talk showed a rather linear way from one person/idea to the other, it was different in Jones'

presentation: Starting with John Bennett a rhizomatic net of people, disciplines and projects spread out. Both

speakers followed the traces and networks of people, inventions and mutual influences. In the end Century's

presentation lead to the development of an (industrial) product while Jones' lead into manifold art projects.

Eva Moraga presented The Computational Center at Madrid University (1969 - 1973), a project made possible by the support of IBM. They gave two high end computers to the University plus a yearly financial donation of 1 Actually it was called the PARC User Interface. 2 Fred Turner uses the terms „boundary object“ and „trading zone“ in his book „From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism“; „boundary object“ taken from Susan Leigh Star and James Greisemer, „trading zone“ coming from Peter Galison. Throughout all panels both terms were frequently used. 18.000€. The Center should have been open to researchers from all over Spain. Its mission was to study automation of research and analysis processes in fields where automation had not been brought in yet, like „Mathematics Linguistics“, „Automatic Generation of Architectonic Spaces“ and „Automatic Generation of Plastic Forms“. IBM had not allowed the University to use the computers for administrative tasks. For that, the Center would have to buy seperate machines from IBM. IBM also influenced the Center by naming the director.

The Center's approach was interdisciplinary, the staff consisted of computer experts with international

experience and artists could apply for scholarships. A research goal would be, for example, to find out the

grammar rules a specific artist would apply when producing his/her work. Moraga's presentation remained within the field of mere facts. She didn't take a critical position regarding IBM's influence or the political situation of Franco-Spain or on how those two together had an impact on the Center's supposed autonomy. Time and Space, the panel's framing constituents, became strangely visible by their absolute absence in her talk.

The goal of Robin Oppenheimer's talk was to show the emergence of new collaborative practices and forms of communication at the intersection of art and engineering in E.A.T.'s „9 Evenings“. In the 10 month long

collaboration between the Greenwich Village art scene and engineers from Bell Labs, artists and engineers had to define a common base to work on. Oppenheimer also used Fred Turner's interpretation of the „boundary object“ and the „trading zone“ to describe this search for bridging difficulties in understanding each other's ideas, in articulating the ideas of one field in a way that was meaningful for the other and finally in being able to create something together.

Oppenheimer mentions that the ethical values of openness and egalitarian collaboration were crucial to this

experiment. I would like to question the notion of collaboration implied here: The artists involved in „9

Evenings“ had already been well established. Their names attracted the audience and still do. At a concurrent

exhibition at Tesla, an art space in Berlin, the descriptions of projects from „9 Evenings“ were headed by the

project's title, the artist and then, almost as a footnote or addendum came the name of the project engineer. So this collaboration had been less egalitarian but rather shows a clear hierarchy of art over engineering.

Contextualization:

None of the panelists spoke about the influence of the futuristic zeitgeist of the 60ies with its perspectives of

landing on the moon, etc. Time was only present as history, the military background of the labs and the

chronological development of technologies invented for military purposes. All projects had in common that they started or were made possible in a field of military research: The Lincoln Labs as an institute of MIT and funded by the US military (Xerox PARC functioning as a commercial follow up in this case); Moraga's project placed in Franco-Spain where it was instrumentalized both by the regime to show off and by IBM (who didn't show moral fibre in collaborating with Franco-Spain, but merely wanted the Center to do research IBM would profit from and maybe even sell their products to the University); and finally Oppenheimer's presentation on E.A.T.'s „9 Evenings“ was again related to military R+D through Bell Labs.

Penalties for the panelists - Discussions:

Time was crucial to this panel in another way: Each speaker got exactly 20 minutes for the presentation, which was too short for each of them. Century and Oppenheimer dealt with it by talking very fast, so that it was hard to follow. Moraga and Jones spoke slower, but unfortunately couldn't finish their presentations. The way that these time constraints were put on this panel was quite impolite towards the speakers and their interesting topics as well as towards the audience. A result of the strictly executed 20-minutes-setup discussions after each presentation were rare and not very lively. Robin Oppenheimer had the advantage that her topic was the most commonly known and got great support from the audience: Artist Gerd Stern (USCO) had attended the „9 Evenings“ and could give an authentic impression of the event.

Moderator or Administrator?

re:place chose to have moderators for the panels, Edward Shanken was the first to go and do the job and interpreted his role in a strictly administrative sense. He didn't give an introduction on the panel's topic, but made clear the „rules of the game“: Each panelist had 20 minutes time for a presentation or otherwise would have „their heads cut off“ (sic!), followed by 10 minutes for discussion, this was repeated four times so that in the end 30 minutes would remain for a panel discussion. To structure a conference into different thematic panels suggests to me an explanation of why certain microhistories are combined. It literally wants an introduction to be made that could open up discussion in the final round. To structure the panel in this way, to introduce, sum up, and contextualize would have been the role of the moderator. And this was badly missing.

(http://www.proce55ing.net/copyright.html:)

"Processing was started in Fall 2001 by Ben Fry and Casey Reas. Fry was a PhD candidate at the MIT Media Laboratory and Reas was an Associate Professor at the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea. While Fry and Reas were employees of these institutions, Processing began as a personal initiative and development took place during the night and weekends through 2003. MIT indirectly funded Processing through Fry's graduate stipend and Ivrea indirectly funded Processing through Reas's salary. Due to his research agreement with MIT, all code written by Fry during this time is copyright MIT.

In summer 2003, Ivrea funded four individuals to work on the project for a few months. This resulted in Dan Mosedale's preprocessor using Antlr and Sami Arola's contributions to the graphics engine. The code for these elements are both copyright 2003 Interaction Design Institute Ivrea.

In August 2003, Reas left the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea and in June 2004, Fry left the MIT Media Laboratory. The code and complete reference written since June 2004 are copyright Ben Fry and Casey Reas.

Portions of the code were written by other contributors and are attributed in the source code. For example, portions of the graphics engine were written by Karsten Schmidt. There are many contributions to the Exhibition and Examples on the Processing.org website and these are attributed in context.The Reference for the Language and Environment are under a Creative Commons license which makes it possible to re-use this content for non-commercial purposes if it is credited."

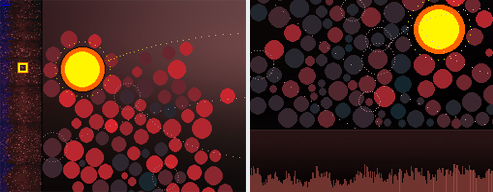

eamples of artworks done with processing:

- Golan Levin, "The Dumpster"- LIA

- Casey Reas, "Microimage"

- Ben Fry, "Valence"

- Josh On, "Inequality"

- Marius Watz, "C Drawer"

- Ed Burton, "SodaProcessing"

- JonahBrucker-Gohen, "Tech Support"

- Justin Manor, "Presidential Discombobulator"

- Alvaro Cassinelli, "Khronos Projector"

- Art+Com, "Process"

- Philip Worthington, "Shadow Monsters"

- rAndom international, "Pixel Roller"

"Processing is written in Java and enables the creation of Java Applications and Applets within a carefully designed set of constraints. It uses a 2D/3D Java rendering API that is a cross between postscript-style imaging in 2D and 3D rendering with OpenGL. Through developing Processing as a solid and general technical platform, we hope teaching the concepts of interaction and computer programming will focus more on the qualities and content of medium, rather than the technology." (http://www.groupc.net/2002/proce55ing/index.html)