"semi automatic ground environment"

"semi automatic ground environment"

"project Charles" was started at MIT to develop a demo, they developed their Whirlwind computer, a real-time system, furhter.

"project Charles" was also the starting point for the Lincoln Labs, whre the SAGE project was continued from 1954 on. IBM cooperated with MIT on this project, which made it the dominat company in computer industry.

The outcome of SAGE was AN/FSQ-7, the largest computer ever built. It used more than 50.000 tubes and because of the tubes' unreliability, a SAGE system always consisted of two computers for backup - a dual processor so to say.

impact of SAGE for further computer developments; online systems, interactive computing, rel-time computing, data communications with modems.

background-info:

"The Whirlwind project was very expensive and made up the bulk of the Office of Naval Research budget. As a result, it became the target of congressional budget cutters, who threatened to reduce the allocation from $1.15M to $250K in 1951. Through intense lobbying by MIT, the Whirlwind computer was ultimately adopted by the U.S. Air Force for use in its new SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) air defense system, which became operational in 1958 with more advanced display capabilities."

(http://design.osu.edu/carlson/history/lesson2.html)

an official video:

video showing how SAGE was used:

<< preface

it is also meant to be an additional resource of information and recommended reading for my students of the prehystories of new media class that i teach at the school of the art institute of chicago in fall 2008.

the focus is on the time period from the beginning of the 20th century up to today.

>> search this blog

2008-07-03

>> SAGE project

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

8:33 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer history

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Ed Zajac, "A Two Gyro Gravity Gradient Altitude Control System", 1962

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

8:01 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer animation,

computer graphics,

Labs,

scientific visualization

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Lincoln Labs and history of computer graphics

One of the most important and influential birthplaces of HCI

was the work on interaction and graphics centered around

the TX-2 computer at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory in the

1960’s [25]. For example, it is hard to imagine the

innovation that happened at Xerox PARC in the ‘70s having

been possible without the foundation that Lincoln Labs

provided.

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

7:43 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer graphics,

computer history,

HCI

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> theses @ Lincoln Labs

http://www.billbuxton.com/Lincoln.html

On the website of his Lincoln Labs History project, Bill Buxton collected links to some influential theses written at the Lincoln Labs.

The project furthermore provides information about the history, the proceedings of the 2005 conference on the Lincoln Labs in the 1960ies and especially about the TX-2 computer.

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

7:35 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer history,

Labs

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> MIT's Lincoln Labs

excerpt from wikipedia:

excerpt from wikipedia:

"In 1950, MIT undertook a summer study, named Project Charles, to explore the feasibility of establishing a major laboratory focused on air defense. The summer study recommended the establishment of a laboratory, named Project Lincoln to be operated by MIT for the Army, Navy and Air Force. The name "Project Lincoln" was chosen because the Laboratory sits near the towns  of Bedford, Lexington and Lincoln, MA, and the names "Project Lexington" and "Project Bedford" were already taken by other DOD efforts.

of Bedford, Lexington and Lincoln, MA, and the names "Project Lexington" and "Project Bedford" were already taken by other DOD efforts.

In the early years, the most important developments to come out of Lincoln Lab were SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment), a nationwide network of radar and anti-aircraft weapons linked to digital computers.

Some of the earliest computer graphics and user interface research was done at the laboratory, including Sutherland's Sketchpad system. Research into "packetized speech," (now VoIP) done in collaboration with other researchers, led to the creation of UDP.

MIT's relationship with Lincoln Lab has come under intense scrutiny several times. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, growing disaffection with U.S. involvement in Vietnam led to student demonstrations demanding that MIT halt defense research, MIT responded by spinning off the semi-autonomous Draper Labs entirely and moving all on-campus classified research to Lincoln Lab."

Bill Buxton's presentation on the history of the Lincoln Labs on ePresence.tv

http://epresence.tv/Presentation/3

from their own history page:

Created in 1951 as a federally funded research center of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lincoln Laboratory was focused on improving the nation's air defense system through advanced electronics.

The Laboratory’s inception was prompted by the Air Defense Systems Engineering Committee’s 1950 report that concluded the U.S. was unprepared for the threat of an air attack. Because of MIT’s management of the Radiation Laboratory during World War II, the experience of some of its staff on the Air Defense Systems Engineering Committee, and its proven competence in electronics, the Air Force was convinced that MIT could provide the research needed to develop an air defense that could detect, identify, and ultimately intercept air threats.

MIT’s Whirlwind computer of the 1940s gave promise of solving these challenges. Building on the Whirlwind’s digital technology, early research at Lincoln Laboratory tackled the design and prototype development of a network of ground-based radars and aircraft control centers for continental air defense—the Semiautomatic Ground Environment (SAGE). Significant technical advances.

MIT’s Whirlwind computer of the 1940s gave promise of solving these challenges. Building on the Whirlwind’s digital technology, early research at Lincoln Laboratory tackled the design and prototype development of a network of ground-based radars and aircraft control centers for continental air defense—the Semiautomatic Ground Environment (SAGE). Significant technical advances.

Over the 50+ years since the Laboratory’s establishment, the scope of the problems has broadened from the initial emphasis on air defense to include space surveillance, missile  defense, surface surveillance and object identification, communications, and air traffic control, all supported by a strong advanced electronic technology activity. The Laboratory’s Millstone Hill radar, completed in 1957, utilized the first all-solid-state, programmable digital computer for real-time tracking of objects in space. In addition to its role in developing technology basic to the ballistic missile early warning system, the Millstone Hill facility was the first radar to detect the Soviet Sputnik satellites and later served as a tracking station for Cape Canaveral launches. [...]

defense, surface surveillance and object identification, communications, and air traffic control, all supported by a strong advanced electronic technology activity. The Laboratory’s Millstone Hill radar, completed in 1957, utilized the first all-solid-state, programmable digital computer for real-time tracking of objects in space. In addition to its role in developing technology basic to the ballistic missile early warning system, the Millstone Hill facility was the first radar to detect the Soviet Sputnik satellites and later served as a tracking station for Cape Canaveral launches. [...]

In the early 1960s, MIT Lincoln Laboratory initiated the development of satellite communications systems for national defense, resulting in the launch of eight experimental communications satellites.

Nonmilitary Applications

The Laboratory demonstrated advances in autonomous spacecraft control, the use of solid state devices to ensure long-term spacecraft reliability, and the development of mobile earth terminals for secure communications systems.

In the early 1970s, MIT Lincoln Laboratory began an active program in civil air traffic control, emphasizing radar surveillance, collision avoidance, hazardous-weather detection, and the use of automation aids in the control of aircraft.

In the 1980s, the Laboratory accomplished significant experiments in compensating for the effects of atmospheric turbulence by using adaptive optics and developed a high-power laser radar system.

In the 1990s, work for other government agencies included sensor development for NOAA and NASA. The Laboratory developed an advanced land imaging instrument as part of NASA’s New Millennium Program.

To support its aggressive approach to advanced systems development, MIT Lincoln Laboratory has also maintained a leadership role in basic research in surface and solid-state physics and materials relevant to solid-state physics.

The Laboratory performed the initial research for the development of the semiconducting laser and designed an infrared laser radar to develop techniques for high-precision pointing and tracking of satellites."

The Laboratory has also made significant contributions to the early development of modern computer graphics, the theory of digital signal processing, and the design and construction of high-speed digital signal processing computers. Signal processing remains a key element of many Laboratory programs, including special-purpose high-throughput processors.

The Laboratory has advanced the technology of speech coding for digital processing. Speech coding and recognition, along with automatic translation, are continuing areas of interest."

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

5:01 PM

0

replies

tags -

Labs

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Seymour Papert, LOGO

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

4:30 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer programming language

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Small Talk, Shazam (animation SW), Dynabook

http://www.newmediareader.com/book_samples/nmr-26-kay.pdf

"Much of the design of SHAZAM, their animation tool, is an automation of the media with which animators are familiar: movies consisting of sequences of frames which are a composition of transparent cels containing foreground and background drawings. Besides retaining these basic concepts of conventional animation, SHAZAM incorporates some creative supplementary capabilities. Animators know that the main action of animation is due not to an individual frame, but to the change from one frame to the next. It is therefore much easier to plan an animation if it can be seen moving as it is being created. SHAZAM allows any cel of any frame in an animation to be edited while the animation is in progress. A library of alreadycreated cels is maintained. The animation can be singlestepped; individual cels can be repositioned, reframed, and redrawn; new frames can be inserted; and a frame sequence

can be created at any time by attaching the cel to the pointing device, then showing the system what kind of movement is desired. The cels can be stacked for background parallax; holes and windows are made with transparent paint. Animation objects can be painted by programs as well as by hand. The control of the animation can also be easily done from a Smalltalk simulation. For example, an animation of objects bouncing in a room is most easily accomplished by a few lines of Smalltalk that express the class of bouncing objects in physical terms."

--> McLaren

--> Baecker, GENESYS

+++++++++++++++

SMALL TALK

... is an object-oriented programming language, developed at Xerox PARC by Alan Kay, Adele Goldberg, et.at. in the 1970ies. Influences come from LOGO (as mentioned below), Lisp, Simula and Sketchpad.

Seymour Papert, a great influence on Kay, was creating computer systems for children to use creatively on the other side of the United States, at MIT. There, he developed LOGO (see ◊28). Kay’s previous work on FLEX had sought to create a computer that users could program themselves. This work led to the definition of object-oriented programming (inspired, in part, by Sutherland’s “Sketchpad” (◊09)). From Papert’s work, Kay saw how far this idea could be carried, and refined his notion of why it was important. The next stage of Kay’s work in this area culminated in Smalltalk.

http://www.newmediareader.com/book_samples/nmr-26-kay.pdf, page 2:

Kay on Papert's Papert’s influence in 1990:

“I was possessed by the analogy between print literacy and LOGO. While designing the FLEX machine I had believed that end users needed to be able to program before the computer could become truly theirs—but here was a real demonstration, and with children! The ability to ‘read’ a medium means you can access materials and tools generated by others. The ability to ‘write’ in a medium means you can generate materials and tools for others. You must have both to be literate. In print writing, the tools you generate are rhetorical; they demonstrate and convince. In computer writing, the tools you generate are processes; they simulate and decide.” (“User Interface: A Personal View,” 193)

(http://www.smalltalk.org/smalltalk/TheEarlyHistoryOfSmalltalk_Abstract.html)

"Early Smalltalk was the first complete realization of these new points of view as parented by its many predecessors in hardware, language and user interface design. It became the exemplar of the new computing, in part, because we were actually trying for a qualitative shift in belief structures--a new Kuhnian paradigm in the same spirit as the invention of the printing press-and thus took highly extreme positions which almost forced these new styles to be invented." (Alan Kay)

++++++++++++++++

DYNABOOK

"I remembered a wonderful phrase of Marshall McLuhan. He said, I don't know who discovered water, but it wasn't a fish. The idea is if you are immersed in a context you can't even see it. So we decided to follow Seymour Papert's lead and instead of trying to design for adults we would try and see what this Dynabook of the future would be like for children and then maybe hope some of it would spill over into the adult world. So children were an absolutely critical factor here. " (Alan Kay, http://www.artmuseum.net/w2vr/archives/Kay/01_Dynabook.html#)

The concept of the Dynabook is what later on became the laptop. The target audience would be children. The Dynabook ran on Small Talk. Kay was one of the main developers and was involved in the creation of the 1-Laptop-per-Child group.

Alan Kay about Humans and Media:

“Devices” which variously store, retrieve, or manipulate information in the form of messages embedded in a medium have been in existence for thousands of years. People use them to communicate ideas and feelings both to others and back to themselves. Although thinking goes on in one’s head, external media serve to materialize thoughts and, through feedback, to augment the actual paths the thinking follows. Methods discovered in one medium provide metaphors which contribute new ways to think about notions in other media."

Alan Kay on Dynabook:

(http://www.smalltalk.org/smalltalk/TheEarlyHistoryOfSmalltalk_Abstract.html)

"Most ideas come from previous ideas. The sixties, particularly in the ARPA community, gave rise to a host of notions about "human-computer symbiosis" through interactive time-shared computers, graphics screens and pointing devices. Advanced computer languages were invented to simulate complex systems such as oil refineries and semi-intelligent behavior. The soon-to-follow paradigm shift of modern personal computing, overlapping window interfaces, and object-oriented design came from seeing the work of the sixties as something more than a "better old thing." This is, more than a better way: to do mainframe computing; for end-users to invoke functionality; to make data structures more abstract. Instead the promise of exponential growth in computing /$/ volume demanded that the sixties be regarded as "almost a new thing" and to find out what the actual "new things" might be. For example, one would computer with a handheld "Dynabook" in a way that would not be possible on a shared mainframe; millions of potential users meant that the user interface would have to become a learning environment along the lines of Montessori and Bruner; and needs for large scope, reduction in complexity, and end-user literacy would require that data and control structures be done away with in favor of a more biological scheme of protected universal cells interacting only through messages that could mimic any desired behavior."

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

4:10 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer animation,

computer history,

Xerox PARC

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

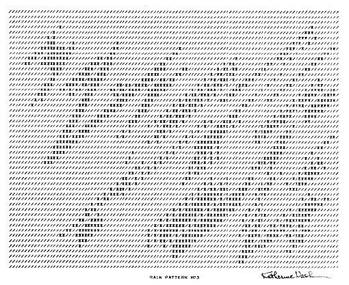

>> Katherine Nash, Richard H. Williams, ART1 (1970)

In 1970, Nash then of the University of Minnesota and Richard H. Williams then of the University of New Mexico and later the University of Minnesota published Computer Program for Artists: ART 1. The authors described three approaches an artist might take to use computers in art:

- The artist can become a programmer or software engineer

- Artists and software engineers can cooperate, or

- The artist can use existing software. At that time, ART 1 existed and she chose this path

ART1 is the result of a collaboration between an artist and an engineer, developed at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of New Mexico.

"ART I in all its detail is somewhat involved. It contains approximately 350 separate statements

written in FORTRAN IV, a programming language. An artist, however, need not concern himself with programming complexities, since the entire program is stored in the computer's memory bank. The program may be obtained by simply using one card that had been key-punched:

/INCLUDE ART1

(*) Computer Program for Artists: ART 1, Katherine Nash and Richard H. Williams, Leonardo, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Oct., 1970), pp. 439-442 (article consists of 4 pages)

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

3:36 PM

0

replies

tags -

artistic software,

computer graphics,

computer programming language

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Bell Labs

http://design.osu.edu/carlson/history/tree/bell.html

Bell Labs in Murray Hill, NJ was a leading research contributor in computer graphics, computer animation and electronic music from its beginnings in the early 1960s. Initially, researchers were interested in what the computer could be made to do, but the results of the visual work produced by the computer during this period have established people like Michael Noll and Ken Knowlton as pioneering computer artists.

Edward Zajac produced one of the first computer generated films at Bell Labs in 1961, which demonstrated that a satellite could be stabilized to always have a side facing the earth as it orbited. This film was titled A two gyro gravity gradient altitude control system. Ken Knowlton developed the Beflix (Bell Flicks) animation system in 1963, which was used to produce dozens of artistic films by artists Stan VanDerBeek, Noll, Knowlton and Lillian Schwartz. Ken Knowlton and Leon Harmon experimented with human pattern perception and art by perfecting a technique that scanned, fragmented and reconstructed a picture using patterns of dots (such as symbols or printer characters.) Ruth Weiss created in 1964 (published in 1966) some of the first algorithms for converting equations of surfaces to orthographic views on an output device.

The artistic/scientific/educational image making efforts at Bell Labs were some of the first to show that electronic digital processing (using the IBM 7094 computer) could be coupled with electronic film recording (using the Stromberg-Carlson 4020 microfilm recorder) could be used to make exciting, high resolution images. With the dozen or so films made between 1963 and 1967, and the many more films after that, they showed that computer animation was a viable activity. Zajac's work, Sinden's films (eg, Force, Mass and Motion) and studies by Noll in the area of stereo pairs (eg, Simulated basilar membrane motion) were some of the earliest contributions to what is now known as scientific visualization.

Turner Whitted arrived at Bell Labs from NC State (PhD - 78), and proceeded to shake the CGI world with an algorithm that could ray-trace a scene in a reasonable amount of time. His film, The Compleat Angler is one of the most mimicked pieces of CGI work ever, as every student that enters the discipline tries to generate a bouncing ray-traced ball sequence. Whitted was also very instrumental in the development of various scan line algorithms, as well as approaches to organizing geometric data for fast rendering. In 1983, Whitted left Bell Labs to establish Numerical Designs, Ltd. in Chapel Hill. NDL was founded with Robert Whitton of Ikonas to develop graphics toolkits for 3D CGI. Key developments of NDL include

- NetImmerse 3D Game Engine

- MAXImmerse 3D Studio MAX Plug-in

- rPLUS Photorealistic Rendering Software

Whitted also had a faculty appointment at UNC, and in 1997 joined the graphics division at Microsoft. He is an ACM Fellow, and received the 1986 SIGGRAPH Graphics Achievment award for his simple and elegant algorithm for ray-tracing. He is now lead contact for the Graphics group and the Hardware Devices group at Microsoft, where he is investigating alternative user

timeline: (did not work on my computer)

http://www.alcatel-lucent.com/wps/portal/BellLabs/History/Timeline

- they developed the programming language C (1970), WLAN (1990), DNA machine prototypes, large scale integrated circuits (in the 60ies), the transistor (50ies),

- Claude Shannon wrote his publication about Information Theory there, Bardeen, Brattain and Shockley received the Nobel Prize for their invention of the transistor

| Name | Came from | Went to | Comments |

| Ed Zajac | |||

| Ken Knowlton | MIT | Wang | |

| Stan VanderBeek | |||

| Lillian Schwartz | |||

| Michael Noll | Newark College of Engineering | White House Office of Science and Technology, USC | |

| Frank Sinden | |||

| Turner Whitted | NC State | UNC, Microsoft | |

| Bella Julesz | |||

| C. Bosche | |||

| Leon Harmon | |||

| Ruth Weiss | |||

| Max Mathews | |||

| Emmanuel Ghent | |||

| Laurie Spiegel | |||

| Jerry Spivack | |||

| Doris Seligmann | |||

| Carl Machover |

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

3:29 PM

0

replies

tags -

Labs,

timeline

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Francis Alÿs

--> VDB has material!

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

2:41 PM

0

replies

tags -

artists,

media art,

psychogeography

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Larry Cuba, interviewed by Gene Youngblood, 1986

article from: http://www.well.com/~cuba/VideoArt.html

article from: http://www.well.com/~cuba/VideoArt.html

CALCULATED MOVEMENTS

An Interview with Larry Cuba

by Gene Youngblood

Larry Cuba is one of the most important artists currently working in the tradition known variously as abstract, absolute or concrete animation. This is the approach to cinema (film and video) as a purely visual experience, an art form related more to painting and music than to drama or photography. Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter, Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, Norman McLaren and the Whitney brothers are among the diverse group of painters, sculptors, architects, filmmakers and video and computer artists who have made distinguished contributions to this field over the last 73 years.Insofar as it is understood as the visual equivalent of musical composition, abstract animation necessarily has an underlying mathematical structure; and since the computer is the supreme instrument of mathematical description, it's not surprising that computer artists have inherited the responsibility of advancing this tradition into new territory. Ironically, very few artists in the world today employ the digital computer exclusively to explore the possibilities of abstract animation as music's visual counterpart. John Whitney, Sr. is the most famous, and rightly so: he was the first to carry the tradition into the digital domain, and his book Digital Harmony is among the most rigorous (if also controversial) theoretical treatments of the subject. But for me Cuba's work is by far the more aesthetically satisfying. Indeed, if there is a Bach of abstract animation it is Larry Cuba.

Words like elegant, graceful, exhilarating or spectacular do not begin to articulate the evocative power of these sublime works characterized by cascading designs, startling shifts of perspective and the ineffable beauty of precise, mathematical structure. They are as close to music---particularly the mathematically transcendent music of Bach---as the moving-image arts will ever get.

Cuba has produced only four films in thirteen years. The best known are 3/78 (Objects and Transformations) (1978) and Two Space (1979). The imagery in both consists of white dots against a black field. In 3/78 sixteen "objects," each consisting of a hundred points of light, perform a series of precisely choreographed rhythmic transformations against a haunting, minimal soundtrack of the shakuhachi, the Japanese bamboo flute. Cuba described it as “an exercise in the visual perception of motion and musical structure." In Two Space, patterns resembling the tiles of Islamic temples are generated by performing a set of symmetry operations (translations, rotations, reflections, etc.) upon a basic figure or "tile." Twelve such patterns constructed from nine different animating figures are choreographed to produce illusions of figure-ground reversal and afterimages of color. This is set against 200 year old Javanese gamelan music. Both films have won numerous awards and have been exhibited at festivals around the world . Calculated Movements, Cuba's first work in six years, premiered in July at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and was also included in the film and video show of SIGGRAPH '85, the international computer graphics conference. It is a magnificent work, destined to join 3/78 and Two Space as a classic of abstract animation. It represents a formal departure from its predecessors. Whereas they were produced on expensive vector graphic equipment at institutional facilities, using a mainframe and minicomputer respectively, Calculated Movements was produced at Cuba's studio in Santa Cruz on the Datamax UV-1 personal computer with Tom DeFanti's Zgrass graphics language. This is a raster-graphic system that allowed Cuba to work for the first time with solid areas and "volumes" rather than just dots of light. The result, both in design and dynamism, is strongly reminiscent of the films of Oskar Fischinger.

Computer animation is neither film nor video---those are simply media through which a computer's output can be stored, distributed and displayed. Previously Cuba released his work only on film, but Calculated Movements is available on both film and video. We talked about the theory and practice of abstract animation, about the computer as an instrument of that practice, and about the production of Calculated Movements.

GENE: There's a widespread belief that mathematics and intuition are somehow antithetical; yet the outstanding characteristic of your work is a graceful musicality that feels profoundly intuitive, even spiritual.

LARRY: I appreciate your saying that because that's clearly my goal . Music does do that, and it has an underlying mathematical structure, although I think no one's really clear on how or why it affects us the way it does, what the rules are. A lot of people are working on that and have theories about it. It seems my job is to see how we can do it graphically.

What I'm trying to do is, I think, very difficult. The creative process here appears to be so much different than from most art forms---using mathematics to create pictures, trying to make them affect us the way music does. ' How do I create these things? . . . " I think it comes from paying attention to things that affect me. When I see visuals that elicit that response I think about why, where it came from, what is the quality? In a sense, this is what abstraction is about: what's the essence without the details? I'm always searching for that. In computer graphics today there's, this great push toward simulating reality, especially natural phenomena. Realistic simulations of plants, for example. Plants are beautiful, so naturally the simulations are beautiful. Plants, mountains, trees, the pattern water makes when it goes over a rock-these are evocative in the same way music is. But I want to know why. I don't want to simply reproduce the pattern; I want to know what it is about the pattern that evokes that feeling. And what's the relation between that pattern and its mathematical description?

What they're finding now as they attempt to simulate things like trees is that there's a balance between total randomness and an order that's very predictable. Leaves of a tree are different in some ways and the same in others. So there's a delicate balance between the order which makes them the same and the randomness which makes them different. It's what makes the tree so aesthetically satisfying. And that's where the underlying mathematics comes in. In my work, I start with a very ordered system and continually add the variations which make it more and more interesting.

GENE: When you show your films in person, you frequently talk about the history of hand-drawn abstract animation and show examples of work by Fischinger and McLaren and others.

LARRY: That's to establish an appropriate context for the work. Because typically the interest in these films comes from an interest in the technology, the fact that it's computer graphics or computer animation. It seems the major assumed goal is to push the state of the art technologically. I'm not interested in that. My work is not part of that big race for the flashiest, zoomiest, most chrome, most glass, most super-rendered image. My interest is experimental animation as the design of form in motion, independent of any particular technology used to create it. The underlying problems of design in motion are universal to everyone working in this tradition whether they use the computer or not. So in that sense what I do is not "computer art.”

On the other hand the technology is clearly important. If you think about the process used in abstract animation it does become important that you’re using a computer in the way it affects your vocabulary. Because if you start with these mathematical structures you can discover imagery that you have not previsualized but have ‘found’ within the dimensions of the search space. Certainly every artist is engaged in some form of dialogue with their tools and their medium, whether it's brushes on paint and paper or a video synthesizer or a computer. But my tool is the mathematics and the programming that depend on a computer as the medium to execute it. So in that sense the computer adds a new dimension to this field of exploration which started with Gina and Corra, the Italian Futurists who are attributed with the earliest abstract films in 1912. They were talking 20th century dynamism. Today we're talking mathematics.

GENE: Do you have a formal background in math?

LARRY: I don’t use any math more advanced than what you learn in high school. Just algebra. But I do have an interest in mathematics as a domain of thought. It’s a lot like art---a world in itself, apart from everyday reality yet also underlying everyday reality. And the more advanced the mathematics the more abstract it is. It becomes more a world of its own. You can say the same about art as it be comes more abstract.

GENE: How do you work? Do you think up an image and then work backward from image to an equation?

LARRY: A little of both. It's ironic, but I find that when I visualize a specific image and program it up, it never looks as interesting as I thought it would. But that's the beginning. I can see what's wrong with it and that's where I start making changes. It's a real exploration through a space of imagery that I'm led to through this dialog, so that every experiment leads to the next experiment.

GENE: That's the whole point of experimental work. It's research.

LARRY: Or art. Someone once asked what I mean by the term "experimental film." What makes them experimental? I said because they’re not previsualized. They're the result of experiments and dialog with the medium. And he said, 'Well, all art is like that, that's what art is." I said all art is like that but all film is not. We're much more used to films being preconceived, both in content and execution. Even many people with whom I share the same intent will listen to a piece of music, come up with images, storyboard them and animate them . So that by the time they get to the production stage the result is almost a foregone conclusion.

That's much less of a dialog than my approach and in that sense it's not as experimental. Also there's the danger that the music is carrying the piece: take away the sound and there's not much left. In my work, the visuals come first. I'm trying to discover what works visually, so I never start with music. That would be starting with a composition that already exists, and composition is the problem. I don't have an image of the final film or even any of the scenes before I start programming. I only have basic structural ideas that come from algebra, or from the nature of the [computer] drawing process, or from the hierarchical structure of the items in the scene and how they will dance---the choreographic movements from a mathematical point of view.

GENE: Calculated Movements differs from your earlier films more than they differ from one another.

LARRY: The most obvious difference comes directly from the hardware. The other films were done on vector systems, so I was using dots. Going to the Zgrass machine meant not only going down from a mainframe to a mini to a micro but also going from vector to raster graphics. So this is my new palette, so to speak. New in two ways: I could draw solid areas so that my form became delineated areas instead of just dots, and I had four colors: white, black, light grey and dark gray. Every film I've made was done on a different system. This is the only piece I've made on this machine. So the evolution of my work is directly parallel to the evolution of systems I've used.

Two Space was not composed in real time. It was done in the traditional manner of writing the program, running it on a computer in animation mode where it takes several seconds per frame, then it goes to film, then the film is processed, and only then can you see it move. As a result, the rhythmic structure of Two Space is rather limited. There isn't much variation. The pacing is very much like the gamelan music I used on the soundtrack, regular and continuous. The advantage was that working in animated time imposed no limit on the complexity of the image. As long as I was willing to wait it would continue to draw dots. So the images could be dense and they could be of any arbitrary formulation---the computation required to calculate where the dot goes could be arbitrarily complex. For 3/78, I used a real time system. When I ran my programs I could see the animation immediately. That feedback allowed me to deal with a more varied rhythmic structure. There's much more variation in 3/78, so it feels more musical in the western sense of polyrhythmic structure. But there was a trade-off because there's a limit to what can be calculated and drawn in real time, and that imposed a limitation on its visual complexity. With Calculated Movements, I was back working in animated time. Consequently, I don't think it's as rhythmic as 3/78 in the sense of a variety of movements. 3/78 is one continuous transformation from beginning to end whose movements start and stop and change speed according to a fairly complex score without much repetition, whereas each event in Calculated Movements has its own fixed internal rhythm. It comes and goes and there isn't much variation other than that. So in that sense it's more like Two Space.

GENE: It feels very fluid and elegant to me. Can you describe the compositional strategy?

LARRY: There are five movements that alternate between two types. The odd-numbered movements are each structured as a single event about a minute long in which ribbon-like figures follow a single trajectory against a middle gray background, and each scene represents a structural variation on this theme.

In the first movement a single rib bon appears, follows a trajectory and disappears; it's followed by another ribbon, then another, and so on, all following the same path. So there are no transformations in space but a large transformation in time---that is, the figures are shifted out of phase only in time but not two dimensionally. Another option is to spread them out in a two-dimensional pattern so they can be traversing this path simultaneously. So in the third movement they're shifted both in time and space. Also, because the figures are longer they overlap and form a dense array. They appear, go through the trajectory and disappear. In the fifth movement, they’re also shifted in time and space but they're shorter in length, so they look more like a flock of birds.

The strategy for the even-numbered movements, in contrast, was a collection of forty short events ranging from one and a half seconds to five seconds, orchestrated to appear and disappear at different intervals. Each event follows the same basic structure of a trajectory, repetition of the figure and some transformation spatially and temporally of each repetition. I designed these events using a random number generator that selected values for each parameter from within a predetermined range. Many events were generated this way, then I selected and orchestrated them intuitively. So the overall strategy for Calculated Movements is a two dimensional pattern whose parameters are: What is the path? How many figures are there? How far apart are they? What are the dimensions of each ribbon? And the phasing---how far apart in time are they? This is essentially an evolution of the Two Space approach. All of Two Space came from variations of the basic figure whose parameters were fixed for the whole film. The next step was to start varying those parameters to get more degrees of freedom. And that's Calculated Movements.

GENE: What about sound?

LARRY: Larry Simon and Craig Harris did the odd-numbered movements based on my suggestions. They used a computer-controlled Yamaha DX-7. These are the scenes that follow the same path and have the feel of being one long event, so they have one type of very melodic music almost Philip Glass style.

The other scenes were more difficult because their structure is more intricate- more isolated events. Rand Weatherwax did the sound for these using an Emulator Two, a digital sampling device like the Fairlight or the Synclavier that has a built-in sequencer. I found it would be easy to match the sequencing of sound events with graphics events by programming into the sequencer the same temporal structure as the images. So, because we synced up sonic events with graphic events you might say that the composition-in the sense of when notes appear and disappear-comes directly from the underlying structure that I had composed for the graphics. But when it came to what sounds to plug in for each event, Rand would pull out one of his library of effects and would modify it until I was satisfied. So in that sense it was a collaboration not unlike my collaboration with John Whitney as programmer for Arabesque. John didn't actually write the programs but he had very specific ideas. So who composed Arabesque? Well, it's John’s film creatively; I only worked as programmer, but I think if someone else had programmed it, it would have come out differently.

GENE: How long did you work on the visual composition?

LARRY: About two and a half years. The first few months are always spent developing tools in the particular language you're using. The language itself is a tool but then you create your own tools with it---called macros or sub routines---to do generalized classes of things. That’s a reason why the generalized approach takes more time. For 3/78, I spent about three months developing the tools that would allow me to manipulate geometric figures and score them with different phasing and patterns and so on. Then came the matter of using that tool to score a specific sequence. So first I developed the tools and then I made the film.

But with Calculated Movements the tools evolved simultaneously with the visual composition. I started making serious progress only when I got a Lyon-Lamb video animation system about two years ago. Then I could do extended scenes on tape so I could see what I was doing. I'd program the scenes then run the computer for ten or twenty hours to produce the animation. I did have some preview during the still phase/ while I was developing the program. I could look at some images to make sure the program was running right. Then I’d run it and look at the tape, and that was the first time I actually saw the images move. At that point l’d frequently realize I needed a whole other set of tools so I'd rewrite the entire system and experiment some more. Over two years I generated about ninety minutes of working material, about a hundred individual shots. That represents an evolution of programs. So there was an evolution of the tool simultaneously with the evolution of the pictures-to the extent that I'd get way down the line and look back at the early pictures and realize I couldn't generate those pictures anymore because the software had evolved. I'd opened up new dimensions and closed off others. So it represents my own personal evolution. As Jane Veeder likes to say, the artist is the work in progress. This is two years of working on me. The films are like progress reports. They represent where I am at this point in the evolution.

Gene Youngblood on "Calculated Movements":

"Calculated Movements...was produced on a raster-graphic system that allowed Cuba to work for the first time with solid areas and "volumes" rather than just dots of light. The result, both in design and dynamism, is strongly reminiscent of the films of Oskar Fischinger.

Words like elegant, graceful, exhilarating or spectacular do not begin to articulate the evocative power of these sublime works characterized by cascading designs, startling shifts of perspective and the ineffable beauty of precise, mathematical structure. They are as close to music --- particularly the mathematically transcendent music of Bach --- as the moving-image arts will ever get."

--- Gene Youngblood, Video and the Arts

fromthe EVL-website:

"Calculated Movements by Larry Cuba is an example of early video art using software developed at the Electronic Visualization Laboratory (EVL). The video has a minimalist/ambient original sound piece.

In the 1970s the computer graphics for the first Star Wars film (1977) was created by Larry Cuba at the Electronic Visualization Laboratory (EVL) (at the time known as the Circle Graphics Habitat) at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Calculated Movements is a sample of Cuba's later work."

from: www.well.com/user/cuba/Mediagramm.html

"Larry Cuba must be considered the most distinguished practitioner of "computer graphics", for, though he has created only three films in the last 20 years, each one of them remains a masterpiece of Visual Music that resonates with fresh interest each time it is viewed-- the same replay-value that fine auditory music possesses.

The origin of Cuba's excellence arises from several factors, one of them undoubtedly native genius, but that can not be measured or discussed so easily. Larry was born in 1950 in Altanta, Georgia-- home of Gone With the Wind, Coca Cola, Delta Airlines and the 1996 Olympic Games. He received his Master's Degree from California Institute of the Arts, a unique college near Los Angeles, which includes parallel schools of Dance, Music, Film, Theater, Fine Arts, and Writing. The Cal Arts faculty included abstract animator Jules Engel, Expanded Cinema critic Gene Youngblood, and special- effects wizard Pat O'Neill. The animation studios at Cal Arts also sit next door to the Gamelan rooms which host a staff of Indonesian instructors, with both a Balinese and a Javanese gamelan orchestra-- so that while the animators work, they can often hear the mellow bell harmonies such as those Larry would later use for his film Two Space. Engel and Youngblood definitely instilled in all the students a love for the great masters of Visual Music from the pioneers Walter Ruttmann, Oskar Fischinger and Viking Eggeling to the living (then) California masters James Whitney, Jordan Belson and Harry Smith. For Larry this certainly meant a refinement of his aesthetic perception and standards, which would make him prepare his own later films consciously, with extra care and no compromise.

Pat O'Neill, in addition to the inspiration from his fascinating, exquisitely-complex animation/live-action films, influenced a generation of Cal Arts students, including Adam Beckett, Robbie Blalock, Chris Casady and Larry Cuba, who all worked on special effects for the landmark 1977 science-fiction feature Star Wars.

Next to the factor of artistic taste, the most important aspect of Larry Cuba's success in Computer Graphics probably rests in the fact that he himself programs his own films. Beginning with the "pioneers"-- like Stan Vanderbeek and Lillian Schwartz who both used Ken Knowlton's Beflix program to create numerous "computer graphic films" which all look painfully alike, awkward in their accretion of oozing grids-- most artists have relied on software packages prepared by a technician or endemic to a particular hardware system. Their artistic compositions had to cope with the parameters, demands and limitations of a program over which they had no control. John Whitney, one of the senior pioneers of Computer Graphics (for whom Larry Cuba prepared the program of the 1975 Arabesque), complained until his dying day about the limitations of his hardware and software, which never allowed him to create simultaneous real-time parallel visual and auditory compositions-- and, for example, usually left him employing an automatic color-mapping instead of a more sophisticated nuancing of hues that might have suggested an equivalent of auditory tone colors.

In his own films, Larry has avoided aspects such as texture and color which can not be adequately modulated to produce genuinely satisfying artistic effects. In 3/78 and Two Space (1979) he uses only points of light against a pure black background, which if properly printed on dense black-and-white film stock and correctly projected onto a film screen (no video substitutes, please), produce after- images in the viewers' eyes that sometimes trace trajectories, sometimes add luminous sparkles of gold and iridescent colors to the dots-- a kind of predictable optical phenomenon also employed by James Whitney and Jordan Belson for "magical" effects in their films.

3/78 , created in Chicago with Tom DeFanti's Graphic Symbiosis System [GRASS], consists of sixteen "objects", each composed of 100 points of light, some of them geometric shapes like circles and squares, others more organic shapes resembling gushes of water. Each object performs rhythmic choreography, precisely programmed by Cuba to satisfy mathematic potentials. The fascinating aesthetic results exude musicality-- a lyrical splash of mirror-image fountains bouncing and rebounding, percussive snaps of imploding squares leaving gashes of afterimage. The spare sound score for Kazu Matsui's shakuhachi flute perfectly complements the contemplative visual images.

By comparison, Two Space presents lush, full-screen image- patterns which parallel the layered continuities of classical gamelan music. Using a programming language called RAP at the Los Angeles firm Information International Inc. (III), Larry was able to systematically explore the classic 17 symmetry groups, which Islamic artists had long since discovered as the basis for their abstract temple decorations. Since Cuba's images again consist of white points of light on a black background, the movement of these dots create patterns by their movement, and imply other patterns in the black matrix by not occupying certain "negative space". Within the film's nine-minute duration, one senses an increasing complexity, an infinite potential-- and a dazzling climax of exquisite, "imaginary" complexity, as the viewer recognizes the eye's complicity in manufacturing afterimages and negative space illusions.

For Calculated Movements (1985), Larry again tried something quite different, using Tom DeFanti's Zgrass language on a raster- graphic system, which allowed him to program solid areas and volumes instead of merely the vector dots of the previous two films. It also allowed Cuba to choose four "colors": black, white, light grey and dark grey. These new parameters let Larry work with something he had long admired in Oskar Fischinger's black-and-white Studies: the complex choreography of simple forms. In five episodes, he alternates single events involving ribbon-like figures following intricate trajectories, with more complex episodes consisting of up to 40 individual events that appear and disappear at irregular intervals. Separate electronic sound scores underline the different nature of the odd and even episodes.

Larry Cuba's residency at ZKM will allow him to explore yet another territory. Silicon Graphics, until recently, could only be used with pre-programmed modeling packages, which made it easy for artists and animators to use, but unsatisfactory for someone like Larry Cuba, who prepares his films through algorithmic concepts at the programming level, generating his musical quantities with mathematical quantities. The new Python software available for Silicon Graphics at ZKM will allow Larry to program a new film there, and possibly discover a new, unexplored world of Visual Music sensations."

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

10:32 AM

0

replies

tags -

computer animation,

text,

video

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Theodor W. Adorno, quotes from "Resumé about Culture Industry", 1963

"Culture Industry is concious top-down integration of its users."

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

7:56 AM

0

replies

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Theodor W. Adorno, "The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass-Deception", 1944

from: http://www2.cddc.vt.edu/marxists/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/adorno.htm

from: http://www2.cddc.vt.edu/marxists/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/adorno.htm

THE sociological theory that the loss of the support of objectively established religion, the dissolution of the last remnants of pre-capitalism, together with technological and social differentiation or specialisation, have led to cultural chaos is disproved every day; for culture now impresses the same stamp on everything.

Films, radio and magazines make up a system which is uniform as a whole and in every part. Even the aesthetic activities of political opposites are one in their enthusiastic obedience to the rhythm of the iron system. The decorative industrial management buildings and exhibition centers in authoritarian countries are much the same as anywhere else. The huge gleaming towers that shoot up everywhere are outward signs of the ingenious planning of international concerns, toward which the unleashed entrepreneurial system (whose monuments are a mass of gloomy houses and business premises in grimy, spiritless cities) was already hastening. Even now the older houses just outside the concrete city centres look like slums, and the new bungalows on the outskirts are at one with the flimsy structures of world fairs in their praise of technical progress and their built-in demand to be discarded after a short while like empty food cans.

Yet the city housing projects designed to perpetuate the individual as a supposedly independent unit in a small hygienic dwelling make him all the more subservient to his adversary – the absolute power of capitalism. Because the inhabitants, as producers and as consumers, are drawn into the center in search of work and pleasure, all the living units crystallise into well-organised complexes. The striking unity of microcosm and macrocosm presents men with a model of their culture: the false identity of the general and the particular. Under monopoly all mass culture is identical, and the lines of its artificial framework begin to show through. The people at the top are no longer so interested in concealing monopoly: as its violence becomes more open, so its power grows. Movies and radio need no longer pretend to be art. The truth that they are just business is made into an ideology in order to justify the rubbish they deliberately produce. They call themselves industries; and when their directors’ incomes are published, any doubt about the social utility of the finished products is removed.

Interested parties explain the culture industry in technological terms. It is alleged that because millions participate in it, certain reproduction processes are necessary that inevitably require identical needs in innumerable places to be satisfied with identical goods. The technical contrast between the few production centers and the large number of widely dispersed consumption points is said to demand organisation and planning by management. Furthermore, it is claimed that standards were based in the first place on consumers’ needs, and for that reason were accepted with so little resistance. The result is the circle of manipulation and retroactive need in which the unity of the system grows ever stronger. No mention is made of the fact that the basis on which technology acquires power over society is the power of those whose economic hold over society is greatest. A technological rationale is the rationale of domination itself. It is the coercive nature of society alienated from itself. Automobiles, bombs, and movies keep the whole thing together until their leveling element shows its strength in the very wrong which it furthered. It has made the technology of the culture industry no more than the achievement of standardisation and mass production, sacrificing whatever involved a distinction between the logic of the work and that of the social system.

This is the result not of a law of movement in technology as such but of its function in today’s economy. The need which might resist central control has already been suppressed by the control of the individual consciousness. The step from the telephone to the radio has clearly distinguished the roles. The former still allowed the subscriber to play the role of subject, and was liberal. The latter is democratic: it turns all participants into listeners and authoritatively subjects them to broadcast programs which are all exactly the same. No machinery of rejoinder has been devised, and private broadcasters are denied any freedom. They are confined to the apocryphal field of the “amateur,” and also have to accept organisation from above.

But any trace of spontaneity from the public in official broadcasting is controlled and absorbed by talent scouts, studio competitions and official programs of every kind selected by professionals. Talented performers belong to the industry long before it displays them; otherwise they would not be so eager to fit in. The attitude of the public, which ostensibly and actually favours the system of the culture industry, is a part of the system and not an excuse for it. If one branch of art follows the same formula as one with a very different medium and content; if the dramatic intrigue of broadcast soap operas becomes no more than useful material for showing how to master technical problems at both ends of the scale of musical experience – real jazz or a cheap imitation; or if a movement from a Beethoven symphony is crudely “adapted” for a film sound-track in the same way as a Tolstoy novel is garbled in a film script: then the claim that this is done to satisfy the spontaneous wishes of the public is no more than hot air.

We are closer to the facts if we explain these phenomena as inherent in the technical and personnel apparatus which, down to its last cog, itself forms part of the economic mechanism of selection. In addition there is the agreement – or at least the determination – of all executive authorities not to produce or sanction anything that in any way differs from their own rules, their own ideas about consumers, or above all themselves.

In our age the objective social tendency is incarnate in the hidden subjective purposes of company directors, the foremost among whom are in the most powerful sectors of industry – steel, petroleum, electricity, and chemicals. Culture monopolies are weak and dependent in comparison. They cannot afford to neglect their appeasement of the real holders of power if their sphere of activity in mass society (a sphere producing a specific type of commodity which anyhow is still too closely bound up with easy-going liberalism and Jewish intellectuals) is not to undergo a series of purges. The dependence of the most powerful broadcasting company on the electrical industry, or of the motion picture industry on the banks, is characteristic of the whole sphere, whose individual branches are themselves economically interwoven. All are in such close contact that the extreme concentration of mental forces allows demarcation lines between different firms and technical branches to be ignored.

The ruthless unity in the culture industry is evidence of what will happen in politics. Marked differentiations such as those of A and B films, or of stories in magazines in different price ranges, depend not so much on subject matter as on classifying, organising, and labelling consumers. Something is provided for all so that none may escape; the distinctions are emphasised and extended. The public is catered for with a hierarchical range of mass-produced products of varying quality, thus advancing the rule of complete quantification. Everybody must behave (as if spontaneously) in accordance with his previously determined and indexed level, and choose the category of mass product turned out for his type. Consumers appear as statistics on research organisation charts, and are divided by income groups into red, green, and blue areas; the technique is that used for any type of propaganda.

How formalised the procedure is can be seen when the mechanically differentiated products prove to be all alike in the end. That the difference between the Chrysler range and General Motors products is basically illusory strikes every child with a keen interest in varieties. What connoisseurs discuss as good or bad points serve only to perpetuate the semblance of competition and range of choice. The same applies to the Warner Brothers and Metro Goldwyn Mayer productions. But even the differences between the more expensive and cheaper models put out by the same firm steadily diminish: for automobiles, there are such differences as the number of cylinders, cubic capacity, details of patented gadgets; and for films there are the number of stars, the extravagant use of technology, labor, and equipment, and the introduction of the latest psychological formulas. The universal criterion of merit is the amount of “conspicuous production,” of blatant cash investment. The varying budgets in the culture industry do not bear the slightest relation to factual values, to the meaning of the products themselves.

Even the technical media are relentlessly forced into uniformity. Television aims at a synthesis of radio and film, and is held up only because the interested parties have not yet reached agreement, but its consequences will be quite enormous and promise to intensify the impoverishment of aesthetic matter so drastically, that by tomorrow the thinly veiled identity of all industrial culture products can come triumphantly out into the open, derisively fulfilling the Wagnerian dream of the Gesamtkunstwerk – the fusion of all the arts in one work.

The alliance of word, image, and music is all the more perfect than in Tristan because the sensuous elements which all approvingly reflect the surface of social reality are in principle embodied in the same technical process, the unity of which becomes its distinctive content. This process integrates all the elements of the production, from the novel (shaped with an eye to the film) to the last sound effect. It is the triumph of invested capital, whose title as absolute master is etched deep into the hearts of the dispossessed in the employment line; it is the meaningful content of every film, whatever plot the production team may have selected.

The man with leisure has to accept what the culture manufacturers offer him. Kant’s formalism still expected a contribution from the individual, who was thought to relate the varied experiences of the senses to fundamental concepts; but industry robs the individual of his function. Its prime service to the customer is to do his schematising for him.

Kant said that there was a secret mechanism in the soul which prepared direct intuitions in such a way that they could be fitted into the system of pure reason. But today that secret has been deciphered. While the mechanism is to all appearances planned by those who serve up the data of experience, that is, by the culture industry, it is in fact forced upon the latter by the power of society, which remains irrational, however we may try to rationalise it; and this inescapable force is processed by commercial agencies so that they give an artificial impression of being in command.

There is nothing left for the consumer to classify. Producers have done it for him. Art for the masses has destroyed the dream but still conforms to the tenets of that dreaming idealism which critical idealism baulked at. Everything derives from consciousness: for Malebranche and Berkeley, from the consciousness of God; in mass art, from the consciousness of the production team. Not only are the hit songs, stars, and soap operas cyclically recurrent and rigidly invariable types, but the specific content of the entertainment itself is derived from them and only appears to change. The details are interchangeable. The short interval sequence which was effective in a hit song, the hero’s momentary fall from grace (which he accepts as good sport), the rough treatment which the beloved gets from the male star, the latter’s rugged defiance of the spoilt heiress, are, like all the other details, ready-made clichés to be slotted in anywhere; they never do anything more than fulfil the purpose allotted them in the overall plan. Their whole raison d’être is to confirm it by being its constituent parts. As soon as the film begins, it is quite clear how it will end, and who will be rewarded, punished, or forgotten. In light music, once the trained ear has heard the first notes of the hit song, it can guess what is coming and feel flattered when it does come. The average length of the short story has to be rigidly adhered to. Even gags, effects, and jokes are calculated like the setting in which they are placed. They are the responsibility of special experts and their narrow range makes it easy for them to be apportioned in the office.

The development of the culture industry has led to the predominance of the effect, the obvious touch, and the technical detail over the work itself – which once expressed an idea, but was liquidated together with the idea. When the detail won its freedom, it became rebellious and, in the period from Romanticism to Expressionism, asserted itself as free expression, as a vehicle of protest against the organisation. In music the single harmonic effect obliterated the awareness of form as a whole; in painting the individual colour was stressed at the expense of pictorial composition; and in the novel psychology became more important than structure. The totality of the culture industry has put an end to this.

Though concerned exclusively with effects, it crushes their insubordination and makes them subserve the formula, which replaces the work. The same fate is inflicted on whole and parts alike. The whole inevitably bears no relation to the details – just like the career of a successful man into which everything is made to fit as an illustration or a proof, whereas it is nothing more than the sum of all those idiotic events. The so-called dominant idea is like a file which ensures order but not coherence. The whole and the parts are alike; there is no antithesis and no connection. Their prearranged harmony is a mockery of what had to be striven after in the great bourgeois works of art. In Germany the graveyard stillness of the dictatorship already hung over the gayest films of the democratic era.

The whole world is made to pass through the filter of the culture industry. The old experience of the movie-goer, who sees the world outside as an extension of the film he has just left (because the latter is intent upon reproducing the world of everyday perceptions), is now the producer’s guideline. The more intensely and flawlessly his techniques duplicate empirical objects, the easier it is today for the illusion to prevail that the outside world is the straightforward continuation of that presented on the screen. This purpose has been furthered by mechanical reproduction since the lightning takeover by the sound film.

Real life is becoming indistinguishable from the movies. The sound film, far surpassing the theatre of illusion, leaves no room for imagination or reflection on the part of the audience, who is unable to respond within the structure of the film, yet deviate from its precise detail without losing the thread of the story; hence the film forces its victims to equate it directly with reality. The stunting of the mass-media consumer’s powers of imagination and spontaneity does not have to be traced back to any psychological mechanisms; he must ascribe the loss of those attributes to the objective nature of the products themselves, especially to the most characteristic of them, the sound film. They are so designed that quickness, powers of observation, and experience are undeniably needed to apprehend them at all; yet sustained thought is out of the question if the spectator is not to miss the relentless rush of facts.

Even though the effort required for his response is semi-automatic, no scope is left for the imagination. Those who are so absorbed by the world of the movie – by its images, gestures, and words – that they are unable to supply what really makes it a world, do not have to dwell on particular points of its mechanics during a screening. All the other films and products of the entertainment industry which they have seen have taught them what to expect; they react automatically.

The might of industrial society is lodged in men’s minds. The entertainments manufacturers know that their products will be consumed with alertness even when the customer is distraught, for each of them is a model of the huge economic machinery which has always sustained the masses, whether at work or at leisure – which is akin to work. From every sound film and every broadcast program the social effect can be inferred which is exclusive to none but is shared by all alike. The culture industry as a whole has moulded men as a type unfailingly reproduced in every product. All the agents of this process, from the producer to the women’s clubs, take good care that the simple reproduction of this mental state is not nuanced or extended in any way.

The art historians and guardians of culture who complain of the extinction in the West of a basic style-determining power are wrong. The stereotyped appropriation of everything, even the inchoate, for the purposes of mechanical reproduction surpasses the rigour and general currency of any “real style,” in the sense in which cultural cognoscenti celebrate the organic pre-capitalist past. No Palestrina could be more of a purist in eliminating every unprepared and unresolved discord than the jazz arranger in suppressing any development which does not conform to the jargon. When jazzing up Mozart he changes him not only when he is too serious or too difficult but when he harmonises the melody in a different way, perhaps more simply, than is customary now. No medieval builder can have scrutinised the subjects for church windows and sculptures more suspiciously than the studio hierarchy scrutinises a work by Balzac or Hugo before finally approving it. No medieval theologian could have determined the degree of the torment to be suffered by the damned in accordance with the order of divine love more meticulously than the producers of shoddy epics calculate the torture to be undergone by the hero or the exact point to which the leading lady’s hemline shall be raised. The explicit and implicit, exoteric and esoteric catalogue of the forbidden and tolerated is so extensive that it not only defines the area of freedom but is all-powerful inside it. Everything down to the last detail is shaped accordingly.

Like its counterpart, avant-garde art, the entertainment industry determines its own language, down to its very syntax and vocabulary, by the use of anathema. The constant pressure to produce new effects (which must conform to the old pattern) serves merely as another rule to increase the power of the conventions when any single effect threatens to slip through the net. Every detail is so firmly stamped with sameness that nothing can appear which is not marked at birth, or does not meet with approval at first sight. And the star performers, whether they produce or reproduce, use this jargon as freely and fluently and with as much gusto as if it were the very language which it silenced long ago. Such is the ideal of what is natural in this field of activity, and its influence becomes all the more powerful, the more technique is perfected and diminishes the tension between the finished product and everyday life. The paradox of this routine, which is essentially travesty, can be detected and is often predominant in everything that the culture industry turns out. A jazz musician who is playing a piece of serious music, one of Beethoven’s simplest minuets, syncopates it involuntarily and will smile superciliously when asked to follow the normal divisions of the beat. This is the “nature” which, complicated by the ever-present and extravagant demands of the specific medium, constitutes the new style and is a “system of non-culture, to which one might even concede a certain ‘unity of style’ if it really made any sense to speak of stylised barbarity.” [Nietzsche]

The universal imposition of this stylised mode can even go beyond what is quasi-officially sanctioned or forbidden; today a hit song is more readily forgiven for not observing the 32 beats or the compass of the ninth than for containing even the most clandestine melodic or harmonic detail which does not conform to the idiom. Whenever Orson Welles offends against the tricks of the trade, he is forgiven because his departures from the norm are regarded as calculated mutations which serve all the more strongly to confirm the validity of the system. The constraint of the technically-conditioned idiom which stars and directors have to produce as “nature” so that the people can appropriate it, extends to such fine nuances that they almost attain the subtlety of the devices of an avant-garde work as against those of truth. The rare capacity minutely to fulfil the obligations of the natural idiom in all branches of the culture industry becomes the criterion of efficiency. What and how they say it must be measurable by everyday language, as in logical positivism.

The producers are experts. The idiom demands an astounding productive power, which it absorbs and squanders. In a diabolical way it has overreached the culturally conservative distinction between genuine and artificial style. A style might be called artificial which is imposed from without on the refractory impulses of a form. But in the culture industry every element of the subject matter has its origin in the same apparatus as that jargon whose stamp it bears. The quarrels in which the artistic experts become involved with sponsor and censor about a lie going beyond the bounds of credibility are evidence not so much of an inner aesthetic tension as of a divergence of interests. The reputation of the specialist, in which a last remnant of objective independence sometimes finds refuge, conflicts with the business politics of the Church, or the concern which is manufacturing the cultural commodity. But the thing itself has been essentially objectified and made viable before the established authorities began to argue about it. Even before Zanuck acquired her, Saint Bernadette was regarded by her latter-day hagiographer as brilliant propaganda for all interested parties. That is what became of the emotions of the character. Hence the style of the culture industry, which no longer has to test itself against any refractory material, is also the negation of style. The reconciliation of the general and particular, of the rule and the specific demands of the subject matter, the achievement of which alone gives essential, meaningful content to style, is futile because there has ceased to be the slightest tension between opposite poles: these concordant extremes are dismally identical; the general can replace the particular, and vice versa.

Nevertheless, this caricature of style does not amount to something beyond the genuine style of the past. In the culture industry the notion of genuine style is seen to be the aesthetic equivalent of domination. Style considered as mere aesthetic regularity is a romantic dream of the past. The unity of style not only of the Christian Middle Ages but of the Renaissance expresses in each case the different structure of social power, and not the obscure experience of the oppressed in which the general was enclosed. The great artists were never those who embodied a wholly flawless and perfect style, but those who used style as a way of hardening themselves against the chaotic expression of suffering, as a negative truth. The style of their works gave what was expressed that force without which life flows away unheard. Those very art forms which are known as classical, such as Mozart’s music, contain objective trends which represent something different to the style which they incarnate.

As late as Schönberg and Picasso, the great artists have retained a mistrust of style, and at crucial points have subordinated it to the logic of the matter. What Dadaists and Expressionists called the untruth of style as such triumphs today in the sung jargon of a crooner, in the carefully contrived elegance of a film star, and even in the admirable expertise of a photograph of a peasant’s squalid hut. Style represents a promise in every work of art. That which is expressed is subsumed through style into the dominant forms of generality, into the language of music, painting, or words, in the hope that it will be reconciled thus with the idea of true generality. This promise held out by the work of art that it will create truth by lending new shape to the conventional social forms is as necessary as it is hypocritical. It unconditionally posits the real forms of life as it is by suggesting that fulfilment lies in their aesthetic derivatives. To this extent the claim of art is always ideology too.

However, only in this confrontation with tradition of which style is the record can art express suffering. That factor in a work of art which enables it to transcend reality certainly cannot be detached from style; but it does not consist of the harmony actually realised, of any doubtful unity of form and content, within and without, of individual and society; it is to be found in those features in which discrepancy appears: in the necessary failure of the passionate striving for identity. Instead of exposing itself to this failure in which the style of the great work of art has always achieved self-negation, the inferior work has always relied on its similarity with others – on a surrogate identity.